Nicole C. Kirk

Reviewed by: D. G. Hart

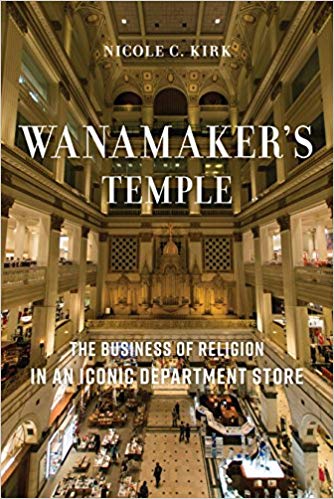

Wanamaker’s Temple: The Business of Religion in an Iconic Department Store, by Nicole C. Kirk. New York University Press, 2018. Hardcover, 288 pages, $28.95 (Amazon). Reviewed by OP ruling elder D. G. Hart

Readers of New Horizons of a certain vintage who grew up in the Philadelphia area may remember arranging to meet a family member or friend at the eagle in the Grand Court of Wanamaker’s Center City department store. Those same people may also remember going to Wanamaker’s during the days between Thanksgiving and Christmas when the store displayed a Christmas pageant of lights accompanied by carols played on the massive pipe organ. If so, they will certainly want to read Nicole C. Kirk’s new book on the man for whom the store was named, John Wanamaker.

Born in 1838 in Gray’s Ferry, then a rural village outside Philadelphia’s incorporated boundaries, Wanamaker became one of the many rags-to-riches stories synonymous with American success. Though he grew up in relative poverty, Wanamaker opened a men’s store only a few years before the Civil War. With his industry and frugality, this eventually turned into Philadelphia’s first department store, originally called Wanamaker & Brown, before his partner died. The business moved from humble store fronts, to the train depot that Dwight L. Moody used for his 1875 Philadelphia revival, to the building that became a central point for shoppers and tourists at Thirteenth and Market, a block from the old Reading Terminal on one side and City Hall on the other. Wanamaker owned another successful department store in New York City.

These accomplishments positioned him in 1899 to become President Benjamin Harrison’s postmaster general, a position that created controversy when Wanamaker followed the rules of the “spoils system” and fired thirty thousand postal workers to create openings for Republican loyalists.

Despite his ham-handedness as a public official, Wanamaker’s business acumen placed him among the nation’s greatest entrepreneurs. In 1953, Joseph Kennedy, John F. Kennedy’s father, announced the Philadelphian’s induction into Chicago’s Merchandise Mart Hall of Fame, with a statue to prove it.

For anyone interested in American Presbyterianism, Kirk’s remarkably instructive biography shows the flaccid condition to which Protestantism in the United States had descended by 1900. (It also makes anyone with the slightest doctrinal rigor wonder why it took so long for conservatives in the Presbyterian Church to stand up to liberalism.)

Wanamaker’s spiritual roots were in the revivalistic Protestantism that grew out of the Second Great Awakening (associated with Charles Finney) and that animated the businessmen’s revivals of 1858 and Moody’s itinerancy a few decades later. This version of Protestantism also supported the Young Men’s Christian Association as a way to provide safe and healthy havens for those working in American cities. Wanamaker’s first job was with the YMCA. He was also at the forefront of American Sunday schools (then still a relatively novel institution).

His support for these Protestant endeavors led him in 1862 to found a Presbyterian congregation, Bethany Collegiate Church (at Twenty-Second and Bainbridge Streets). The church actually emerged from a Sunday school operation that at its height had six thousand students. As conservative as revivalism and Sunday schools may sound today, Bethany called a series of Presbyterian pastors who were prominent in the social gospel movement.

Wanamaker himself was a progressive Republican who constantly used religion for moral and social improvement. In a revealing passage that concludes an extraordinary chapter on the art Wanamaker collected and displayed in his department store—at a time when these institutions were more than simply a place to sell merchandise—Kirk writes that for Wanamaker, art and commerce went hand in hand. The same was true for Christianity and business.

“Wanamaker wanted to awaken his customers’ souls and invite them to reach a higher morality,” Kirk writes. “To acquire Christian taste was to appreciate beauty, which Wanamaker believed would lift the spirit closer to God.” Accompanying an elevated taste were “the values of trustworthiness, simplicity, control, discipline, and balance” (190).

These virtues did not simply lift “the spirit closer to God” but also transformed practically every aspect of human existence—from ethical convictions and household interiors to artistic expression and politics. Many Protestants believed that Western civilization advanced the cause of Christ. Kirk adds, “Neither the division between commercial and religious nor a separation between ‘profane’ and ‘sacred’ existed for Wanamaker.” His department store was the “material expression” of “matters of the spirit” (203).

No matter that skeptical Americans might have regarded such material Christianity as a crass use of religion for profit, or that orthodox Presbyterians may have argued this was a different religion from Christianity altogether, Wanamaker remained a Protestant in good standing. His children drifted upward to Anglo-Catholic parishes in Philadelphia, but Wanamaker remained a member at Bethany Church. By the time of his death in 1922, he embodied the strands of American Protestantism that had contributed to revivalism, moral uplift, progressive politics, the social gospel, Victorian aesthetics, and Protestant modernism. His life shows that you did not need to study at the University of Chicago with Shailer Mathews or Shirley Jackson Case (two prominent modernists) to believe that you were doing the work of the Lord in adapting Christianity to modern times.

Kirk’s biography only indirectly exposes the bloated character of American Protestantism. Hers is a terrific explanation of the many strands of a successful American Protestant entrepreneur. It also prompts great appreciation for the herculean efforts of Presbyterian conservatives like J. Gresham Machen who sought to preserve a Reformed witness in a church that saw little difference between itself and the world.

July 07, 2024

June 30, 2024

Digital Liturgies: Rediscovering Christian Wisdom in an Online Age

June 23, 2024

Worthy: Living in Light of the Gospel

June 16, 2024

The Shepherd’s Toolbox: Advancing Your Church’s Shepherding Ministry

June 09, 2024

The Unfolding Word: The Story of the Bible from Creation to New Creation

June 02, 2024

The Most Unlikely Missionaries: Serving God’s Kingdom in the Middle Kingdom

May 26, 2024

© 2024 The Orthodox Presbyterian Church